How can I improve my writing? (3 ways)

Want to improve your writing? Here are 3 ways to get better and why they matter.

Adam Woodard

4 min read

If you’re wondering ‘How can I improve my writing?’ or something along those lines, it’s a fair guess that you’ve tried writing already, either for professional or personal reasons. Most people can write to some degree, but many aren’t overly concerned with the quality. For those who are, here are three things you can start doing to improve your writing.

These practices are primarily aimed at those who’ve recently taken an interest in improving their own writing. For those who’ve been at it for a while, it might be a good refresher (or totally unnecessary).

1. Read differently

If you’re writing on a somewhat regular basis, chances are that you’re probably reading, too. The extent to which you read and the way you read can dictate the benefits you extract from the process. The following statement may seem odd or obvious depending on who’s reading, but you shouldn’t read all materials the same way.

For instance, if you pick up a fictional story, you open the book at the first page and read linearly until you get to the end. You follow the story. Those who read non-fiction books with the intent to learn often find themselves re-reading certain sections or even entire pages. They might check footnotes, cross-check information, or look up sources. Reading to improve your writing is a bit like this. You’re not primarily interested in the story (in the case of fiction) or information (in the case of non-fiction), but rather how the author writes. Find an author whose style you like and consider some of the following.

How do they use vocabulary? Does their word choice make the text easier to understand or more difficult? How are their sentences structured? Are there lots of clauses, whether dependent or independent? Do paragraphs stand apart or run into each other? All of these are stylistic choices, and over time you’ll develop your own preferences and personal style. But to do this, you want to expose yourself to other people’s styles first. Make a point of reading different writers with different styles and focus on how they write.

The other benefit, assuming the writers you choose are competent, is that you’ll pick up on proper grammar and vocabulary use – both consciously and sub-consciously. This neatly leads to the next point.

2. Proofread

Proofreading is the application of your knowledge of grammar, spelling, and punctuation. And don’t worry about not being qualified or capable enough to proofread, as few people are at first. The point is to accustom yourself to finding mistakes, either in your own writing or that of others. If you’re proofreading your own work, try to do so at least half a day after you wrote it. Better yet, check it the next day. A fresh perspective can work wonders.

Regardless of whose work you’re proofreading, using track changes or an equivalent is useful both for the proofreader and the author (even if they’re the same person). Over time, you’ll get a sense of how much “red” is on the page. The less there is, the better you’re doing. Another practice to consider is to eliminate all doubt. This means that even if you’re 90% sure that something is correct, that isn’t good enough. Look it up and make sure. Reputable online dictionaries and sites like Grammarist are useful resources in this regard.

Here's a rule of thumb for determining whether you know what you’re doing. Imagine someone is peering over your shoulder while you proofread; someone who might ask you a question at any moment. If you’re not confident that you can provide a satisfactory answer about why you did something a certain way, it’s time to look it up to make sure.

3. Find new excuses to write

This essentially boils down to practice, and the need for it doesn’t disappear just because you already write regularly for work reasons. If you’re writing for professional reasons, chances are you’re bound by some rules regarding style. This is good for the organisation that has the rules, as it maintains a particular voice, but it can stifle a writer who wants to improve. Finding excuses to write enables you to implement what you’ve learned and have total control over what you’re writing and how you write it.

As cliché as it may sound, this could be as simple as writing a diary. The only condition I would add for this is to imagine you’re writing for an audience. Otherwise, consider writing a blog or something similar to get into the habit. If you can get feedback, that’s great. If not, be your own harshest critic. The content and medium are entirely up to you. This also ensures that you have something to proofread, and you can revisit older work periodically to gauge your progress. For instance, if you look back at something you wrote more than two years ago and find no faults in it, either you did a really good job or you haven’t progressed that much. Improvement isn’t a destination, it’s a direction.

BONUS: Try to develop a thick skin

Another cliché is having a bonus point at the end of a list – feel free to judge me.

But really, this one’s important, and not just because a primary list of three sounds better than four. If you’re going to expose your writing to feedback or criticism from others, willingly or no, then it’s crucial you develop a thick skin. Almost all feedback, even if delivered negatively, is useful in some way. And just because you had a reason to write something a certain way, that doesn’t mean it was a good reason.

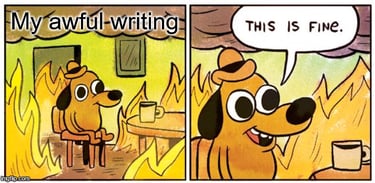

If you feel that criticism of your writing makes you uncomfortable and you find yourself defending or explaining your choices, just take a moment to consider whether your objections are entirely valid. You may discover that your personal connection to your writing makes you more defensive than necessary, especially if you take pride in your work. With time and experience, you’ll learn to discern the difference between valid and invalid criticism – and even then you won’t get it right all the time.